Mastering api call python: Python API Calls with Requests and Httpx

- John Mclaren

- Jan 2

- 13 min read

Making your first API call in Python is way more straightforward than you might think, especially with a library like on your side. All it really takes is importing the library, pointing it to the right URL, and using a simple function like to pull down the data. Most of the time, this data comes back as a JSON object, which Python handles beautifully.

Your First Python API Call with Requests

Diving into APIs can seem complex, but let's cut through the theory and get our hands dirty. The best way to learn is by doing, so we'll start with a real example using Python's go-to HTTP library, . It's so intuitive that it’s a big reason why over 51% of developers choose Python as a primary language—the whole ecosystem is built to make tough jobs feel easy.

This hands-on approach is the fastest way to build confidence and see just how accessible web data can be. If you're interested in going beyond APIs, our guide on how to scrape a website with Python explores more direct data-fetching techniques.

Making the Request

First things first, you need the library. If you don't have it, just pop open your terminal and run .

With that installed, you can make an API call in just a handful of lines. We’ll use the JSONPlaceholder API, which is a fantastic free resource for testing and prototyping without needing to sign up for anything.

Let's grab a list of posts from it:

import requests import json

The API endpoint we want to talk to

api_url = "https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts"

try: # This is where the magic happens: we send a GET request response = requests.get(api_url)

# A handy line to check if the request failed (e.g., 404, 500)

response.raise_for_status()

# The API returns JSON, so we convert it into a Python list

posts = response.json()

# Let's just print the title of the very first post to see what we got

if posts:

print(f"Title of the first post: {posts[0]['title']}")except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e: print(f"Uh oh, something went wrong: {e}")

In this script, we send a request to the URL. The method is a great little shortcut that automatically throws an error if the request wasn't successful, saving us from writing a bunch of statements.

Understanding the Response

When you make a successful call, the API sends back a object. This object is packed with useful information, but here are the essentials:

: This is the HTTP status code. You're hoping for , which means "OK."

: The most useful part. It takes the raw JSON text from the response and converts it directly into a Python list or dictionary.

: If you ever need it, this gives you the raw response body as a simple string.

Before we move on, let's quickly recap what makes up a basic API call.

Core Components of a Python API Call

This table breaks down the key pieces of any API request you'll make.

Component | Purpose | Example in |

|---|---|---|

HTTP Method | The action you want to perform. is for retrieving data. | |

Endpoint URL | The specific address where the data or resource lives. | |

Response Object | What you get back from the server after your request. | The variable in our script. |

Status Code | A three-digit code indicating the outcome of the request. | |

Response Body | The actual data sent back by the API, often in JSON format. | or |

Getting these fundamentals down is your ticket to interacting with almost any modern web service.

A successful first API call is a huge milestone. It's the moment you realize you can programmatically tap into the endless ocean of data on the web. This single skill transforms abstract code into tangible results you can see, use, and build upon.

It's a foundational skill for everything from web development to data science. The explosive growth of frameworks like FastAPI, which saw a 30% jump in adoption, is driven by how simple Python makes it to handle these kinds of HTTP requests. You can read more about these trends in the JetBrains Python Developers Survey 2025. With this first step under your belt, you're ready to tackle the real-world challenges ahead.

Handling Authentication, Headers, and Payloads

While public APIs are fantastic for getting your feet wet, the really interesting data is usually behind a lock and key. This is where authentication comes in. You need to prove to the server that you have permission to access its resources.

Making an authenticated API call in Python is all about adding the right credentials to your request, which almost always means tinkering with the headers.

This simple step is the difference between fetching public info and securely interacting with powerful, protected services. Let's walk through the most common ways APIs handle this.

Using API Keys in Headers

The most straightforward authentication method you'll encounter is the API key. Think of it as a simple password for your script—a unique string that identifies your application. Most services will ask you to pass this key in the request headers.

Doing this with the library is a breeze. You just build a Python dictionary for your headers. For instance, if an API doc tells you to provide a key in a header called , your code would look something like this:

import requests import os

Best practice: store keys as environment variables, not in your code!

api_key = os.getenv("MY_AWESOME_API_KEY") api_url = "https://api.example.com/v1/data"

headers = { "X-API-Key": api_key }

response = requests.get(api_url, headers=headers) print(response.json())

See that ? That's important. Never hardcode credentials directly in your script. It’s a huge security risk. Using environment variables is the professional way to keep secrets out of your codebase.

Working with Bearer Tokens for OAuth

Many modern APIs, especially big ones from companies like Google or GitHub, use OAuth 2.0 for authentication. This process usually ends with you getting a Bearer Token.

This token is sent in a special header. The format is very specific: it has to be the word "Bearer," a single space, and then the token itself.

Here’s how you’d put that request together:

access_token = "a-very-long-and-secure-token-string" api_url = "https://api.anotherservice.com/user/profile"

headers = { "Authorization": f"Bearer {access_token}" }

response = requests.get(api_url, headers=headers) print(response.status_code)

Get used to this pattern. You’ll be seeing it a lot when you start working with major web services.

Sending Data with JSON Payloads

So far, we've only been fetching data with requests. But what happens when you need to create or update something on the server? That's where or requests come in, and they require you to send data, also known as a payload.

Instead of stuffing data into the URL, you send it neatly in the body of the request, usually formatted as JSON.

The library makes this dead simple. You create a regular Python dictionary with your data, and when you pass it to the parameter in your request, handles the rest. It automatically converts it to a JSON string and even sets the correct header for you.

import requests

api_url = "https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts"

Here's the data we want to send to create a new post

new_post = { "title": "My New Post", "body": "This is the content of my fantastic new post.", "userId": 1 }

The parameter does all the heavy lifting

response = requests.post(api_url, json=new_post)

print(f"Status Code: {response.status_code}") print(response.json()) When this works, the server will often reply with the very object you just created, now with its own ID, confirming your was successful. Getting comfortable with headers and payloads is absolutely essential for doing any serious work with APIs.

Boosting Performance with Async API Calls in Httpx

Making a single API call in Python is a piece of cake. But what happens when you need to make a hundred? Or a thousand? Firing them off one by one is like going through the express checkout with a full cart, one item at a time. It's a massive, unnecessary bottleneck.

This is where asynchronous programming completely changes the game.

While the library is an old friend—reliable and great for simple, synchronous tasks—it wasn't built for the kind of concurrency modern applications demand. That's where comes in. It’s a next-generation library that gives you the familiar, comfortable syntax of but with powerful async capabilities built right in.

For any serious data gathering, async isn't just a "nice-to-have." It's essential.

The Magic of Async and Await

Think of a standard, synchronous script as someone meticulously following a recipe. They can't start chopping the carrots until they've finished peeling the potatoes. There's a lot of wasted time.

An asynchronous script, on the other hand, is like a seasoned chef in a bustling kitchen. They can put a pot on the stove to boil and, while waiting for the water to heat up, start prepping the vegetables for another dish. No time is wasted.

That’s exactly what and let you do in Python.

is a keyword that flags a function as a "coroutine"—a special type of function that can be paused and resumed.

is the signal you use inside an function. It basically says, "Okay, I'm about to do something that takes a while, like a network request. Go work on something else until I'm done."

This simple but powerful approach allows your program to juggle dozens, or even hundreds, of API calls at once. The result is a dramatic reduction in the total time spent just waiting for servers to respond.

From Sync to Async: A Practical Refactor

Let's see this in action. Say you need to fetch data from ten different API endpoints. With , you'd hit them one after another.

Now, let's see how we can refactor this into a much faster version using and , Python's built-in library for running these coroutines.

import httpx import asyncio import time

async def fetch_url(client, url): """An async function to fetch a single URL.""" response = await client.get(url) print(f"Fetched {url} with status: {response.status_code}") return response.json()

async def main(): """The main coroutine to run all tasks concurrently.""" urls = [f"https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts/{i}" for i in range(1, 11)]

start_time = time.time()

async with httpx.AsyncClient() as client:

tasks = [fetch_url(client, url) for url in urls]

results = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

duration = time.time() - start_time

print(f"\nFetched {len(results)} pages in {duration:.2f} seconds.")if name == "main": asyncio.run(main())

In this async version, we create a single and then build a list of tasks. The real magic happens with , which orchestrates running all these tasks concurrently instead of sequentially.

The performance difference is staggering. A script that might take ten seconds to run synchronously can often be done in just over one second with this async approach.

This shift towards async is a core trend in modern web scraping and data extraction. JetBrains even reports async/await as a fundamental feature in Python APIs, essential for boosting concurrency and handling the unlimited requests needed for e-commerce price monitoring. Explore more on these developing trends in this 2025 backend development guide.

Adopting for your projects gives you the best of both worlds: the easy-to-use API you know from combined with the raw power of non-blocking I/O. For an even deeper dive into asynchronous requests and proxy usage, check out our guide on mastering web scraping with Requests, Selenium, and AIOHTTP.

Building Resilient Scripts with Error Handling and Retries

A script that runs flawlessly on your local machine can easily fall apart in the real world. Why? Because the internet is a messy place. Networks get flaky, servers get overloaded, and APIs hit you with rate limits. An amateur script will crash and burn at the first sign of trouble. A professional one, however, expects failure and knows exactly how to recover.

Building this kind of resilience into your API call Python scripts isn't just a "nice-to-have." It’s absolutely essential for any serious data pipeline that you don't want to babysit 24/7. It all starts with accepting that things will go wrong.

Handling Common HTTP and Network Errors

Your first line of defense is always the classic block. Think of it as a safety net for your API calls. By wrapping your or call in this block, you're prepared for the unexpected. If a DNS server hiccups or the connection times out, your script won't just die.

Instead, it’ll jump to your block, where you can log what happened and decide on the next move.

Here's what that looks like in practice:

import requests

api_url = "https://api.example.com/data"

try: response = requests.get(api_url, timeout=10) # This little line is a game-changer for catching 4xx and 5xx errors response.raise_for_status() print("Request was successful!") except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e: print(f"Something went wrong: {e}")

In this snippet, is a broad catch-all for anything from a dropped connection to a server error flagged by . This simple structure is your foundation for building a robust script.

Implementing Smart Retries with Exponential Backoff

Just catching an error is only half the story. Let's say you get a error. What do you do? Pounding the server with immediate retries is the worst thing you can do. You’ll just add to the server’s load, annoy the API provider, and probably get your IP address blocked.

This is where a much smarter strategy called exponential backoff comes in.

The idea is simple but powerful: with each failed attempt, you wait a progressively longer time before trying again. The first retry might wait one second, the second waits two seconds, the third waits four, and so on. This gives a struggling API a chance to breathe and recover.

Pro Tip: Exponential backoff is the industry standard for a reason. It shows you're a considerate API consumer, dramatically increases your script's success rate, and keeps you from accidentally launching a mini denial-of-service attack on the server.

Let's wrap this logic into a solid, reusable function.

import requests import time

def make_request_with_retries(url, max_retries=5, initial_backoff=1): """Makes a request with exponential backoff retries.""" retries = 0 backoff = initial_backoff while retries < max_retries: try: response = requests.get(url, timeout=10) response.raise_for_status() return response.json() # Success! We got our data. except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e: print(f"Attempt {retries + 1} failed: {e}") retries += 1 if retries < max_retries: print(f"Retrying in {backoff} seconds...") time.sleep(backoff) backoff *= 2 # Double the wait time for the next round else: print("Max retries reached. Moving on.") return None

Here's how you'd use it:

data = make_request_with_retries("https://api.example.com/flaky-endpoint") if data: print("Successfully fetched data:", data)

This function is a workhorse. It’s configurable, tells you what’s happening, and knows when to give up after exhausting all retries. Adopting patterns like this is what elevates your code from a simple script to a production-ready tool that can handle the unpredictable nature of network communication. This is a critical skill for mastering the art of the Python API call.

Navigating Pagination, Proxies, and Blocked Endpoints

Making a single, successful API call is one thing. But what happens when the data you need is spread across hundreds of pages, or the server slams the door shut after your tenth request? This is where the real work begins. Moving beyond a simple script to build a robust data pipeline means mastering pagination and learning how to deal with blocks.

Most APIs won't hand you their entire database in one go. That would be incredibly inefficient. Instead, they serve up data in "pages," and it's on you to request each one sequentially. This process is called pagination, and it's a fundamental concept you'll encounter constantly.

Looping Through Paginated Data

The trick to handling pagination is to look for clues in the API's response. Often, you'll find a 'next page' link or a field telling you the next page number. You then build a loop in your script that keeps fetching data, page by page, until there are no more pages left. This is the only way to ensure you're getting the complete dataset.

Of course, as you start making hundreds or thousands of requests, another problem pops up: getting blocked. Firing off a barrage of requests from the same IP address is a dead giveaway that you're a script, and many servers will block you outright. This is where a proxy is your best friend. A proxy server acts as a middleman, routing your requests through different IP addresses to make your traffic look like it's coming from many different users.

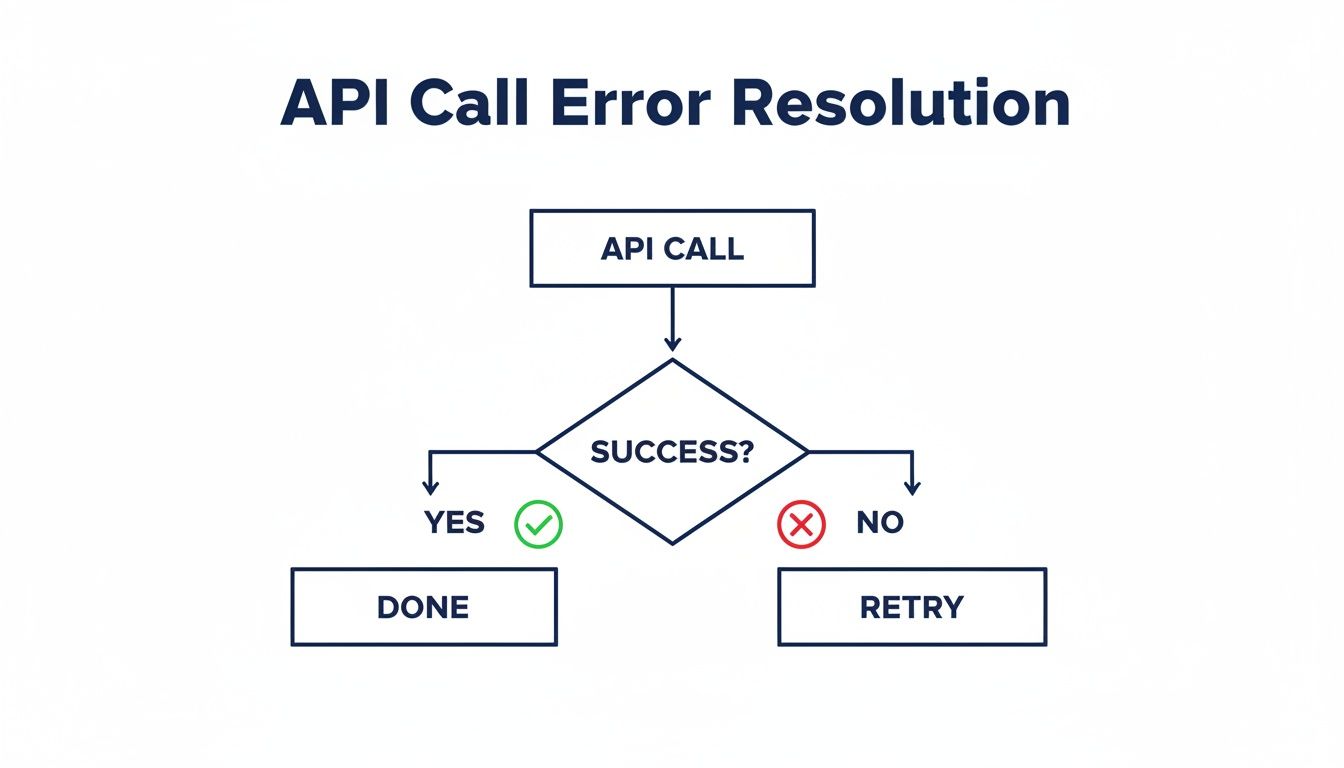

When an API call fails, don't just give up. The most resilient scripts have a solid retry mechanism built in. This simple logic is the core of effective error handling.

The flowchart above illustrates a basic but critical concept: a failed call should trigger a retry attempt. This helps overcome temporary network glitches or server hiccups. For a more technical breakdown, we have a detailed guide where you can master Python requests with a proxy for seamless web scraping.

When Simple Proxies Are Not Enough

Sometimes, just rotating through a list of proxies doesn't cut it. Modern websites and APIs use sophisticated anti-bot systems that can detect more than just a high request volume. They look at browser fingerprints, JavaScript challenges, and behavioral patterns. Trying to outsmart these systems on your own is a frustrating, never-ending battle.

This is exactly why services like ScrapeUnblocker exist. Instead of wrestling with blockades, you make one simple API call to the service. It then takes care of all the messy details—managing proxies, solving CAPTCHAs, and rendering JavaScript—before delivering the clean data back to you.

Your Python script remains focused on what it does best: processing the data. This is particularly important since 51% of Python developers say their primary use case is data processing. A service like ScrapeUnblocker ensures you have a reliable stream of data to work with, letting you focus on analysis, not access.

This approach saves you an enormous amount of development time and headaches by handling the hardest parts of web scraping for you.

Common Questions About Python API Calls

Even after you've got the basics down, a few common questions always seem to pop up when you're working with APIs in Python. From choosing the right library to dealing with a frustrating error message, these are the little hurdles that can really slow you down.

Let's dive into these pain points and get you some clear, straightforward answers so you can write better and more efficient code.

Should I Use Requests or Httpx?

This is probably the number one question I get asked. The honest answer? It really depends on what you're building.

For simple scripts or applications where you're just making a handful of API calls here and there, is a fantastic choice. It's been the go-to for years for a reason: it's incredibly reliable and dead simple to use.

But the moment you need to make dozens, or even hundreds, of API calls as fast as possible, becomes the obvious winner. Its native support for and lets you fire off a ton of requests at once instead of waiting for them one by one. This concurrency can slash your script's runtime from minutes to seconds.

My rule of thumb: Start with if you value simplicity above all. Move to when performance and speed become a priority. Since also has a synchronous client, it can easily be a drop-in replacement for across all your projects.

How Do I Securely Store My API Keys?

I can't stress this enough: never hardcode API keys, tokens, or any other secrets directly in your code. Committing them to a public Git repository is a recipe for disaster. The industry-standard approach is to use environment variables.

Here’s the workflow I use on all my projects:

Create a file named in the root of your project. The very first thing you should do after creating it is add to your file. This stops Git from ever tracking it.

Inside your file, store your keys in a simple format. For example: .

In your Python code, use a library like to load these variables. You can then access them safely using .

This simple practice keeps your sensitive credentials completely separate from your codebase, making everything much more secure.

How Do I Debug Common Errors Like 403 or 429?

API error codes can be cryptic, but they're actually giving you valuable clues about what went wrong.

: Nine times out of ten, a means your authentication is off. The first thing you should do is double-check your API key or bearer token. Is it spelled correctly? Is it expired? Are you sending it in the right header (e.g., )?

: This one is pretty straightforward—the server is telling you to slow down because you've hit its rate limit. The best way to handle this is to implement an exponential backoff strategy in your code, which means you'll wait for progressively longer periods between retries. This gives the API server a chance to breathe.

Comments